I often have to remind myself when working on anything at all, ever: it doesn’t need to be complicated. I’ve written about this on occasion in past blog and substack posts — about bodies of work that are so unapologetically straight-forward. It’s a common thought for younger/emerging artists like myself to think that a body of work, project, or any piece needs to have layers of complexity, a theoretical and thematic purpose and a trove of art-speak in order for it to be accepted into the canon of whatever medium. This is, of course, very, very far from the truth. Alas, this struggle remains persistent. This is also not to say that complex work is lesser-than, rather that complexity must be utilized strategically and with intent, such that the viewer(s) may receive your idea and form their own reading of it. This is also called subjectivity!

As any artist would, I have particular bodies of work that I am most fond of. I could list them all here, but that would be a little much, so I’ll keep it to some highlights of my favorite works that are reminders of this need for simplicity. Also, works that appear complex, but are really just simple ideas with complex interpretations (which I feel is the more common way to work). A simple project is by no means a lesser way to make something. A simple project with complex readings is also not lesser. Complex projects that utilize many facets and styles and media are also not greater than the simpler projects. Ultimately, no one way of constructing a project is better than another. Simple ideas and complex ideas have their own merits, their own strengths and weaknesses, and sometimes both can trick you into thinking it’s the other (and that’s pretty cool).

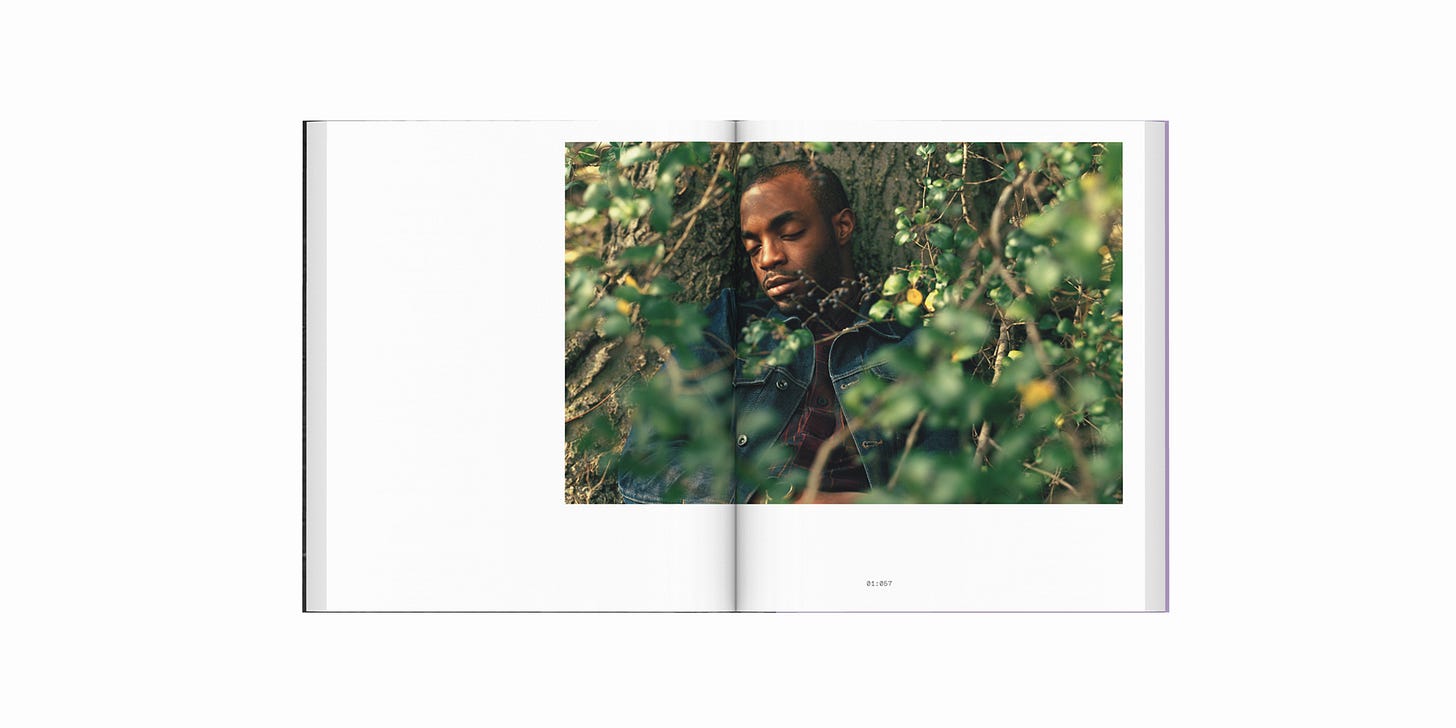

I can think of a complex and incredible body of work, Zora J. Murff’s True Colors which I recently received a copy of. The book is loaded, chapters of images exploring the contemporary space of living as a Black American. This book is not meant to be a simple idea, and the book is not a simple object. It’s phenomenal, and a very important one in today’s discussions on race and photography. It’s a wonderful and meaningful example of a complex body of work that was made strategically as mentioned before, in a way that I, a white man, can receive the message that Murff is communicating and allow me to learn more and form my own understanding of his way of depicting this important topic through art that is both challenging and beautiful.

So, like Murff’s book, there are times and places where a complex idea and complex process and complex interpretation are actually vital to the work. Other times, simplicity is all you need to communicate your idea, to document something and so on, which is the focus of today’s writing.

One of the first books I think of when it comes to a simple idea is Robert Adam’s Summer Nights: Walking that was re-published by Steidl in 2023. The work, all the way to the title, is straight-forward. The older editions of the work left out certain images that were taken when Adams had interactions with police while photographing (of course neighbors in a middle-class neighborhood would be skeptical of someone going around taking pictures in the middle of the night, we’ve all been there). The newer edition includes those images, including one of what he called “the murder house,” which had had multiple sequential deaths take place in it.

The work is immensely poetic and meditative, but also tense and uneasy in the newer edition. It was simply a time for Adams to go make work of what he’s interested in, and it resulted in one of his best-known bodies of work, and it’s so unapologetically straight-forward. This body of work alone has inspired countless artists to come, including Ed Panar (who made his homage work Winter Nights: Walking), and yours truly (with my series Oak Street, which I plan on publishing a new edition of soon — with more pictures!). I often enjoy the bodies of work that are straight-forward down to the title — American Photographs, Walker evans, or Land, Fay Goodwin, or Black and White Things, Robert Frank, the list goes on.

What I find interesting about the artists whose works are titled so simply is that they are often of the generation of photographers making much of their work between the 50’s and the late 70’s. There’s some exceptions to this, of course, with some artists even today titling their works very simply (I’m guilty of it with my installation work Polaroids. Guess what that’s made of). I think that there’s something to be said about the artists who have cemented themselves into the canon of photography that have such simple titles for works that will likely be studied for decades to come. Cape Light, Joel Meyerowitz, or The Americans, Robert Frank, or Chromes, William Eggleston, or Industrial Park Near Irvine California, Lewis Baltz (how much more blunt can you get).

Another body of work that is often referenced in tandem with Adams’ work is John Gossage’s magnum opus The Pond. Gossage has many more works, of course, but the one that most artists know of is this one. It was one of the first sequential narrative bodies of work I encountered, along with Paul Graham’s A Shimmer of Possibility. Gossage’s work is just as unapologetically straight-forward as Adams’ summer walks.

Gossage’s work has also influenced countless photographers to come, it’s very clear the reference between The Pond and Tim Carpenter’s Christmas Day, Bucks Pond Road. I enjoy works like this made in the winter months. I struggle with the summer, but I still get out there and take pictures regardless. These images of winter scenes in wooded areas feel much different to that of the evenings in the summer that Adams photographed. Tim’s Christmas Day, Bucks Pond Road is also something I could consider a “Mini road trip” as he is following a relatively short country road in his hometown, on one day, taking many, many photographs. If memory serves, I believe he even said this was not intended to be a specific body of work, but that it became one after he had gotten the photos back and saw a narrative form. Sometimes, even the simplest of ideas can be made in one day and become one of your most well-known bodies of work.

Carpenter’s work is one that I am deeply connected with, and it’s not only because I love the way his work looks, but also that I have a similar deep connection with central Illinois (he’s from Monticello, IL, which is about an hour away from my hometown). His work speaks to a quiet Midwestern poetry that has been, at least in my social media feeds, growing more and more. Even if it’s not a Midwestern landscape, it seems that people in the 2020’s want quieter photographs, less so the vibrancy and heavily composed work we saw between the 90’s and early 2000’s. But again, maybe that’s just my feed because of who I follow!

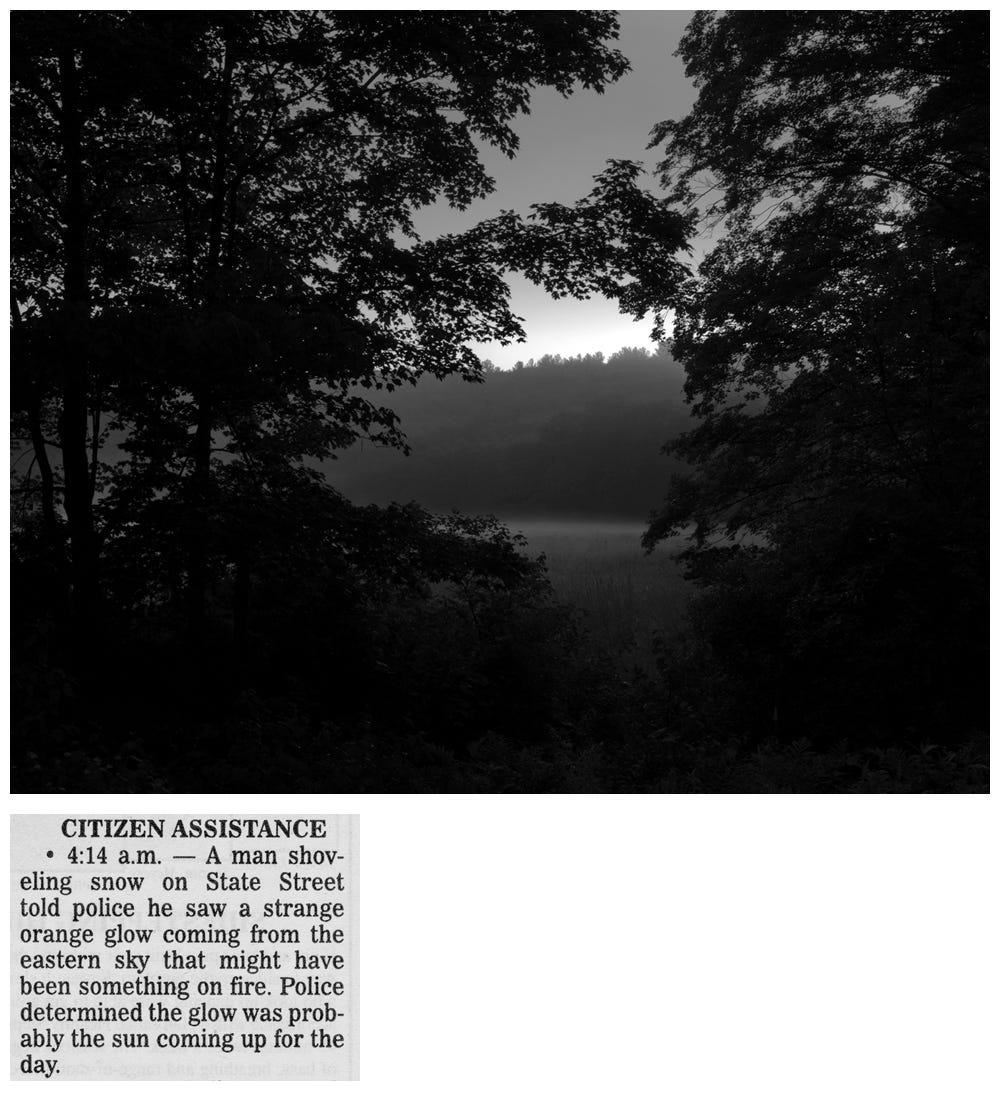

Simple projects can also have layers — they don’t have to be complicated, either. Think of work like Aaron Schuman’s Slant, a project that takes his own images of Amherst, MA, references to Emily Dickenson’s poetry, and excerpts from his hometown newspaper’s section on police calls (that are everything from funny to unnerving). This triad of ideas makes the work so poignant that it has lived in my mind so long that I’m inches away from buying an overpriced used copy online. His own images mimic the humorous, unnerving traits of the newspaper clippings and employ themes of Dickenson’s signature “slant rhymes” within the sequence. It’s not a documentary about Amherst, but simply uses his familiar hometown setting to allow him to utilize Dickenson’s own Amherst connections.

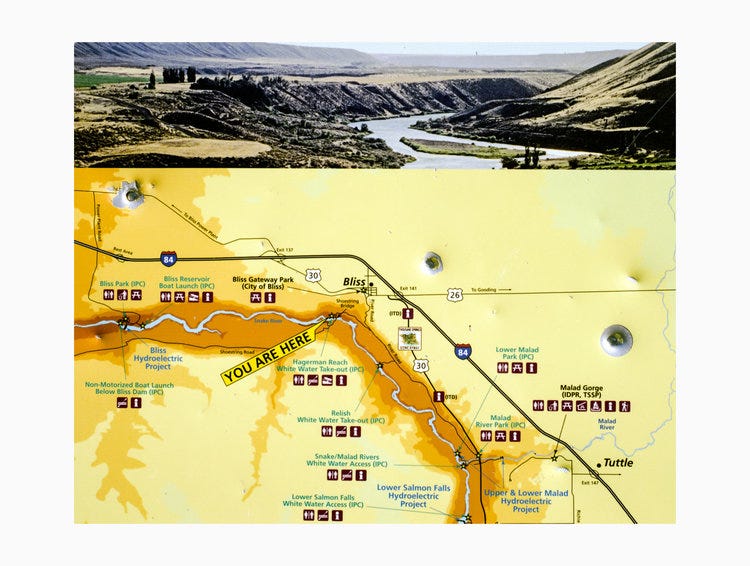

Slant is one of those books that could fall into this category of a simple idea with a complex meaning. Schuman’s work is some of my favorite contemporary photography, his work has been a frequent reference for me when researching ideas for potential projects. Slant also calls to mind another book with a fairly simple concept with layers in its execution: Jon Horvath’s This is Bliss, another book I’ve wanted to add to my library for years.

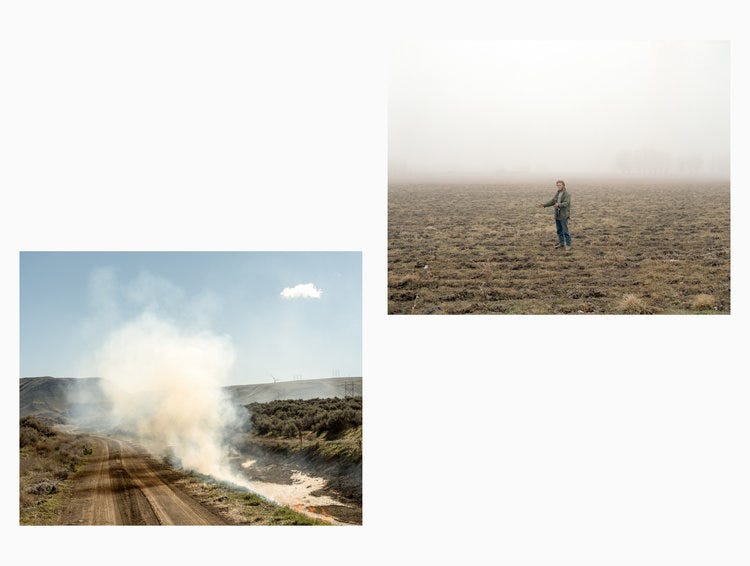

Horvath’s book focuses on Bliss, Idaho, very small town over 80 miles from Boise. He hyper-focused on this town, documenting it and gathering found materials from the town and created a portrait of the town clinging onto its life after the construction of interstate 84 (which stretches from Echo, Utah to Portland, Oregon - side note, I learned that there are sometimes multiple interstates of the same number, there’s also an I-84 in the Northeast that goes from Massachusetts to Pennsylvania, but these two stretches of highway are not connected whatsoever). Horvath’s images are diverse, ranging from landscapes to portraits, day to night, black and white to color, and so on. It shows a small town for what it is today in the aftermath of a major infrastructure development, and that even if there are benefits shortly after its completion, those die off quickly, draining the town of the life it once knew.

This isn’t to depict Bliss, ID as a dreary place, but rather to show the life that is made there, the energy present in such an isolated place that is still connected to the placed beyond. The towns picturesque landscape is of course a draw, but Horvath’s images rarely show the plateaus and river valley that Bliss resides on. He kept this work so constrained to this small place that it created such a complex image with something that doesn’t require much reading into for understanding. However, it’s important to note that any project about place such as this one is far from a simple theme. Place as a conceptual tool is itself a loaded, complex aspect that can latently add many potential readings of the work, such as the differences between the contemporary residents and those of the past, especially of indigenous groups who were the original residents of the area.

In my own work, I think about these things a lot, I try to find ways to honestly represent a place and not over-think the way I make the work. My photographs of rural Illinois from the past few years (and another trip planned in about a month!) are much different from my images in New England, though neither group of photographs from the two places are of specific projects. Tim Carpenter has talked about his process in the past as being a way to collect materials and use the studio to find the connecting threads — for Christmas Day, Bucks Pond Road, that happened to be all of those photos from one day of shooting. I’ve found that collections of photos, even as few as six photos, can be compelling and thought-provoking bodies of work, and have led me to start making small one-off zines in my studio to see if they’re worth putting out into the world.

Photography itself is a very straight-forward act, we point a camera at a scene we found or constructed and record that scene onto a sensor or light-sensitive substrate. We may or may not manipulate the image we record, we may or may not print it big or small, if at all. The image itself is a material for the work. These projects are, themselves, straight-forward just like photography is as a medium of art-making. When working in our studios — be it an office at home or a rented space with a big printer — we all have the same goal in mind: to make a collection of images that communicates an idea. That idea can be anything from a feeling or emotion, to a depiction of a place and the people there, to simply a walk to a pond or along a road. All of these things evoke an emotional and cognitive response from the viewers.

Photography is a generous medium, and some people may ask too much of it, but more often than not, we ask too little and feel that we are floundering. In reality, the medium has given us a democratic means to share work with everybody, a way to show the world as we see it through our literal and figurative lens. You can go as complex and layered as works surrounding social and institutional issues such as Zora Murff’s, or as quiet and poetic as Adams’ work. I’ve often said that I don’t care about photography made for photographers — I stand by that but there’s still plenty of work within that description that I enjoy.

However, the photographic works made with the audience in mind of other photographers falls short, in my eyes, where it is communicating an idea that really only other camera users can understand. These kinds of projects may seem simple to the maker, but are actually quite challenging for someone of a different medium or a non-artist to read. I have recently been showing my new photographs to my partner, who is a writer, and getting her thoughts on the batch of 20-40 pictures I took that morning. There are often photos that we both enjoy, but sometimes I’ll try something a little off the rails and she may not like it as much as me. An example of this was a recent photo I took in a woodland where branches were skirting along the edge of the frame, a near wide-open aperture throwing the background out of focus, such that only those branches on the edges were in-focus. I love this image, but my partner didn’t like it as much as me as she said it “looks like how I see without my glasses.” It makes me think about this idea of work made for an audience of like-minded individuals.

If art is for everyone, and photography is a generous, democratic medium as it is often described, we, as photographers should strive to make work that not only we enjoy, but also that others that do not share a photographic background can enjoy too. That’s not to say that we shouldn’t make images like that at all, but the contrary. I think that the more we play with these ideas that seem simple to us, the camera-users, that we will eventually find a way to use that method in a way that can connect with painters, writers, sculptors, animators, accountants, receptionists, scientists, politicians, construction workers, electricians, stay-at-home parents, and so on.

It’s easy to have big ideas and small idea alike. There’s a thrill in wanting to research and execute a layered, complex project that could be your “next/first big thing.” But history shows that those types of projects seldom get the limelight right away. There’s a beauty in simplicity, an idea can be so carefully articulated with such little themes that allow anyone and everyone to see how you see the world and ultimately, how they see the world.

Thanks for reading, I hope you all have a safe and art-filled rest of the week.

Free to read, as always.

Thanks for the introduction to some new photographers as well as how small ideas can turn into wonderful (and often complex) projects. I'm particularly drawn to the sense of humor and irony in Aaron Schuman's Slant so I'm off to check him out now.