As far back as I can remember, I’ve been re-editing my photographs, I’ve re-scanned my film time and again, I’ve ditched and re-done edits for projects that I hope to send to publishers if I ever feel satisfied with them.

At what point does this become an unhealthy practice? Or is this something that’s expected, that even the biggest, most successful artists have the same processes? I often wonder if Soth or Shore ever look at their scans/prints and think “This still isn’t good enough.”

Perhaps this is something that is inherent in being an artist. We dedicate such large portions of our lives (and money) to a medium/media that we care about deeply. Since 2010, I’ve been interested in photography, but it goes further back than that. I’ve always loved art, the act of making, the satisfaction that comes with taking a photo or making a print that I enjoy. But why is it that despite that initial satisfaction that in the long-term, that satisfaction dwindles?

I’m posing the same question over and over again without much goal in mind to answer it — that’s because I don’t think it can be answered. I’m not a psychologist, though psych has always been an interesting field to me. As a side note, I would love to see an extensive psychological survey of artists (both established and emerging) to see how they perceive their practice and their work. If I were a betting man, I would put my house on the vast majority of artists still feeling that their work could be better.

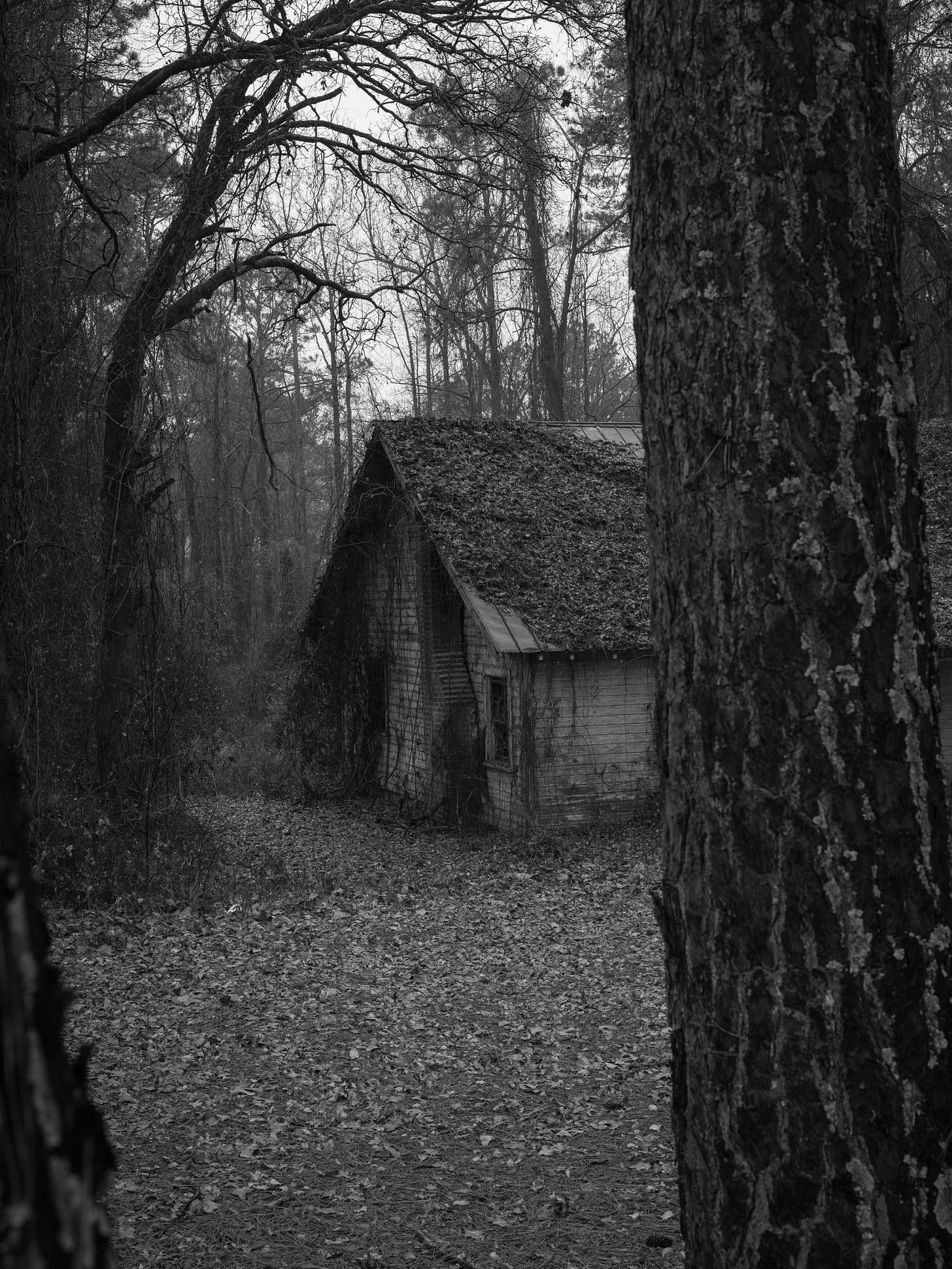

Recently, I’ve been in a battle with treatment of my digital photographs. My most recent shoot was exclusively digital, which lends the photos to being more susceptible to this predicament — do I do color or black and white? Since my work post-MFA has been more gathering materials surrounding themes I’m interested in (rural landscape, spirituality/Christianity, decay, water), I’ve been shooting many different types of cameras and film. Most of the work I shoot in Illinois is on Tri-X 400, so that’s easy enough, no concern…but what about the tone, contrast, brightness…

I can’t win! Thousands of photographs, hundreds of digital contact sheets, going back and forth every day. As I write this, my binder of 35mm film sits next to me as it goes through yet another re-scan. If it’s not the treatment or tonality, it’s the quality of the scan. Granted, the scans I’ve been doing on my current digitizing setup have been the best color I’ve had…but they’re not as sharp as the previous setup…

Again, I can’t win!

My goal in writing today is to allow other artists to understand that this is part of the process, especially as a younger artist. We’re up against a lot — politically, socially, professionally, and it often feels that we have to be that much better, that we need to be like those artists who are doing what we want to do. To some extent, mimicking isn’t a bad thing — you learn a LOT by mimicking. In the time before grad school, much of my work shot in the Midwest was heavily influenced by those artists of the 70’s and 80’s working in contemporary landscape of America shooting in color, the likes of Shore, Meyerowitz, Sternfeld, Eggleston, and so on. Looking back at those film scans and digital photos, there’s a lot that I enjoy about them but I don’t feel as connected to them as I do my recent work from grad school and on. There are gems throughout, even photos that at the time I didn’t like but now I’m all about. Those are the photos that I feel truly satisfied with. Mimicking can get you to a point of understanding your interests, but it’s a fool’s errand to keep it up. I treat those photos as studies, things that I shot for the sake of understanding how I can take a photo using what’s available to me (be it gear, light, subjects, location, etc.).

Looking through my folders of exports from each year, going as far back as 2011, I can see the evolution of interests, but I can also see the pickiness build up over the years as I began my college career and into grad school. However, it was in grad school that I learned to just shoot anything, let the ideas come through the act of taking photos in the field, bringing them back to the studio and looking them over on my own and subsequently with my MFA advisor. While it’s harder to do the latter step of looking over the work with someone else, I can still do the former steps, going out, bringing the pictures back and evaluating.

It’s easy to over-think it — anyone who knows me well is quite aware that I’m a chronic over-thinker (is this also a prerequisite for being an artist?). Going back to my more recent images that I’m struggling with treatment (color vs. black and white), I have to remind myself that 1.) I still have sheets and rolls of film that have yet to be developed of many of the same subjects — I should wait until those come back to decide what to do with color and 2.) I’m allowed to do both for now, these aren’t going into an exhibition, these aren’t being published yet if at all, there are no rules, it’s okay to try a photo in color and like it and also like it in black and white. The photo may find a home in a project where one will work better than the other.

Projects and pools of photos are my biggest ops. I work in projects, usually smaller ones but my MFA allowed me the tools to think bigger and long-term. I’ve been thinking about making small zines of my work, making these for studio practice rather than for selling. This is something that two artists I know do regularly — Ed Panar and Nathan Pearce. These two folks have embedded this into their practice, they both work somewhat similarly in their starkly different environments (the urban landscape of Pittsburgh and Johnstown (Ed) vs. the rural landscape of southern Illinois (Nathan)). These small, personal zines can be very effective to tease out ideas, to see if even a simple concept can be something bigger than a laser-printed, staple-bound book.

I, and many other artists, are very forward-looking, always considering how the work we make will be presented in a book, gallery, installation, and so on. With one of my goals this year to improve my studio practice to be more physical, this mentality is emphasized. The trade-off is allowing this over-thinking to happen, and it’s up to us, the makers, to calm down, realize that this isn’t the Met or the Guggenheim we’re about to show in, it’s our studio, it’s our home, it’s our computer or desk that’s seeing the work. This is where you invite people you trust to visit and look at your work, give them the thoughts that can help put ideas together. Doing this on your own is yet gain, a fool’s errand. Your peers, your friends, your loved ones are the people to help you through this dissatisfaction.

Make art and be happy, that’s all we want to do, so let’s make it happen.